|

Death and the miser an esoteric analysis of the painting by Hieronymus Bosch

A painting in the collection of the National Gallery, Washington, D.C.

Copyright 2013 by Lee van Laer

The original preamble to this piece, as published at the Zen, Yoga, Gurdjieff blog, may be accessed by following the below link:

|

Caveat Emptor. My interpretation of this painting is drawn in its entirety from conclusions I reached during the analysis of the Garden of Earthly Delights; as such, it deviates substantially from the conventional understanding of the painting. The symbolism in the painting is, however, very consistent with the symbolism in the Garden of Earthly Delights, and thus gives important clues as to what the artist actually intended when he painted the painting.

First of all, let's get this straight: evidence suggests the individual in the painting is not a miser. The allegory is about entering the kingdom of heaven; the painting, in my eyes, was likely painted for a specific patron, and he would be the individual we see in the imagery. The patron would not have wished for himself to be depicted as a miser; but rather, a supplicant, struggling to come to terms with the requirements of earthly existence and a wish to enter into heaven. So we are going to refer to the central figure — the "miser" — in the painting as the patron for the remainder of this analysis. And, as we shall see, the painting is a highly unusual and unique wedding portrait.

That heavenly influences suffuse the entire painting is unmistakable, based on the symbolism used in the Garden. We know that Bosch used the color pink to indicate divine or heavenly influence; this is clear from the left-hand panel of the Garden, and indeed the entire painting overall. It's a use of the color, furthermore, which is consistent with other Bosch pieces.

The dominant color in the palette of this piece is pink, indicating that heavenly influences suffuse the environment, but most especially the deathbed of the patron. This is logical if we surmise the patron wishes to have himself shown as surrounded by heavenly influences, that is, on his way to heaven. Rather than a moral lesson or critique of earthly life, then, the painting would be a totemic device intended to surround the patron with a protective aura. Objects of this kind are commonplace in religious traditions, so the piece was, among other things, of eminently practical use, at least from the point of view of the man who originally commissioned the piece.

This purpose is underscored by the presence of the angel, one hand protectively resting on the shoulder of the patron. As usual, Bosch leaves no doubt as to his intentions here: the Angel, with the patron under his protection, is advising death that the patron has a heavenly destiny.

Having established the overall intention and atmosphere of the painting, let's move through it from foreground to background. Bosch has given us a work that must be, like the Garden of Earthly Delights, read in a very orderly manner, like a storybook, and the painting can't be properly comprehended without following the visual narrative flow.

The lance in the foreground points backwards into the field of view, indicating we're supposed to be reading this painting starting with the armored helmet on the right.

|

The armor is a deceptively simple visual symbol, which actually conveys an impressive range of information. First of all, the armor is cast-off; we are at a moment — death — when all of the protections we are clad with in life are useless to us. The empty armor implies nakedness; it is the moment of spiritual truth, when we can no longer hide what we are. Our defenses are not only down, but discarded and helpless, like a husk. |

Secondly, as we know from the Garden of Earthly Delights, armor is worn by the armies of heaven as they introduce temptation to mankind. The empty armor indicates that the moments of temptation are over, and that judgment is at hand. Thirdly, the presence of both a helmet — the mind, or rational thought— and a gauntlet — the hand representing action, or the doing of things — shows that earthly activity has come to an end.

The helmet rests against a pink breastplate or shield, introducing a relationship to higher spiritual influence; and it faces down, as though in shame. (Remember, nothing Bosch includes in his paintings is casual or coincidental; even the least gestures and objects carry meaning.) The inference is that at the end of life, we must trust in heaven.

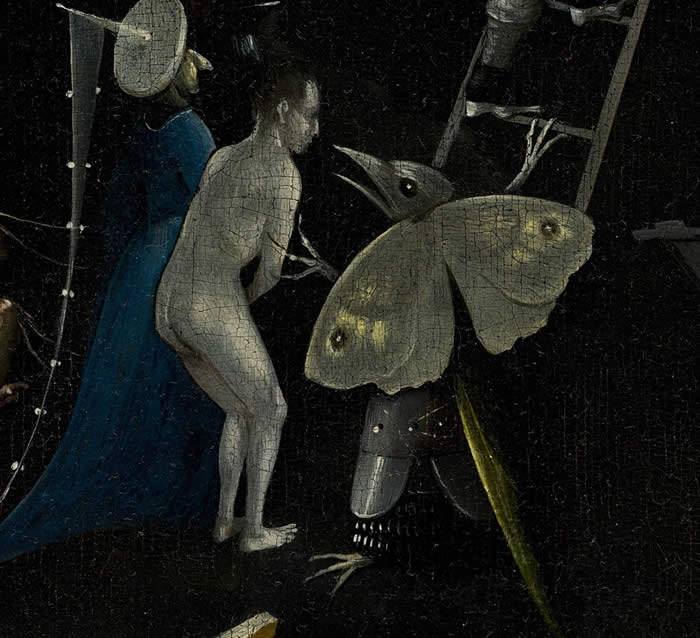

In an unusual and striking visual device, the artist has divided the foreground from the background with a piece of masonry, completely separating the armor and the lance from everything that takes place behind the masonry. The only bridge lying across this particular piece of architecture is the pink cloth on the left, and its companion, another cloth of somewhat darker hue. Bosch used this device to present us with a koan at the foreground of the painting: the masonry represents the passage from earthly — represented by the empty armor, which also represents the body, or corporeal existence — into the realm where the spiritual, or heavenly, acts. Tellingly, the entrance to the spiritual is presided over an imp we are familiar with from the Garden of Earthly Delights: a figure resembling a butterfly or moth, that is, a harbinger of death.

|

|

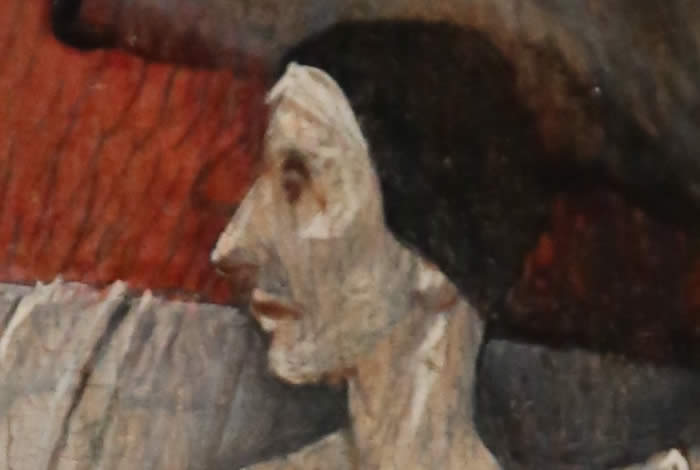

Typical of Bosch, the figure sports a wry expression, his faint smile strongly reminiscent of the cryptic Mona Lisa-like figure in the right hand panel of the Garden. We can consequently presume that this may also be an image of the artist—wise, capable, contemplative, but also mildly irreverent—presenting us with another soliloquy on the meaning of the inner life. Bosch's sense of humor apparently included a penchant for lurking in his landscapes like some antediluvian Hitchcock.

Acting as the gatekeeper between the tellingly empty foreground of the painting — remember, nothing in a painting by Bosch is accidental, and the emptiness indicates how little meaning ordinary life has in comparison to the spiritual life that will follow — the figure, with its absolutely clear parallels to the same figures in the right-hand panel of the Garden, is also an indicator that we are passing into the same level of purgatory, or judgment, that the damned souls are entering in the middle background, or proper central portion, of the Garden's right hand panel.

"Moth" of death, from The Garden of Earthly Delights

This realm, however, carries none of the horrors of hell; suffused with a pink spiritual light, it indicates that the patron is under heavenly influences. Interestingly, the overall tone of the painting, as well as the positioning in the figures, suggest that this painting actually represents an alternate universe to the one of purgatory and hellish damnation in the judgment section of the middle of the right-hand panel of the Garden. Far from being a pessimistic assessment of what must be an inevitable journey towards hell, which is what we see in the garden, it appears to be an optimist's view of the possibility of reaching heaven.

This figure of incipient death appears to be ready to tell us a joke; and indeed, we immediately segue into a humorous segment so typical of Bosch's ability to treat serious spiritual subjects in both a deadly serious, and light and humorous, manner at the same time — a signature of his peculiar and extraordinary genius.

|

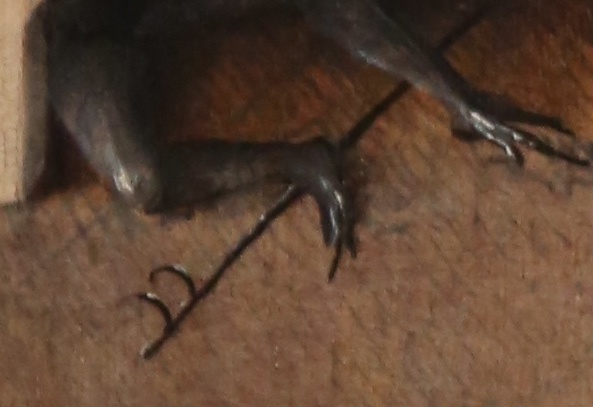

Immediately above the figure, a second tortured harbinger of death sprawls comically under the trunk belonging to the patron. If we were in any doubt about the humorous intention implied by our introductory host, the slapstick pose dispels it. |

The peculiar letter with the red spot on it is a familair device, absolutely identical to the motif from the Garden's right-hand panel, and, as in the Garden, repeated twice:

|

Like the moth, a harbinger of death, the letter serves multiple symbolic purposes. Although it's certain that it represents a message —"death is here," it broadcasts— it also conveys the impression of a handkerchief upon which the evidence of the nuptial chamber is displayed, indicating a loss of virginity. And indeed, the patron is losing his virginity — entering in to a higher reproductive congress with the spiritual realm, which, as we have seen from ample evidence in the central panel of the Garden, is not only implicitly, but also explicitly, sexual in nature, although a much higher form of sexuality to what we are accustomed to.

Looking at the symbolism from this perspective says a bit more about what Bosch is trying to say when he uses the exact same device in the garden. In my view, it's likely the piece was painted subsequent to the Garden—and for someone familiar with it, who specifically asked that a link, or visual reference, to the Garden be included. |

The figure holding the letter is crushed by the stout trunk, which symbolizes the patron's worldly life: the inevitability of death is perpetually obscured by the gross presence and action of life. Just to make the point, however, that there is no escape, the selfsame letter is deposited in the trunk, on the top shelf, an ever present — but tellingly unopened — reminder. Its position in the trunk on the top shelf is an indicator of the fact that the reminder of death ought to be uppermost in a man's mind at all time. (This is probably what the alarmed figure in the Garden holding the letter is trying to convey to the swinestruck lover next to him.)

|

This device of showing distinctive pictorial elements several times in sequence in order to link narrative passages in the painting is familiar to us from the Garden,where, for example, the bagpipes of judgement crop up as the heraldic motif on a flag. |

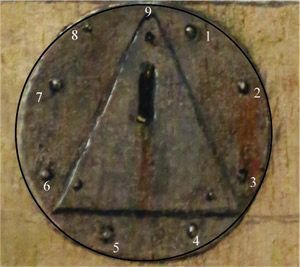

The trunk itelf represents a man's innermost life. It's firmly with a circle containing a triangle. This represents the ubiquitous influence of the holy Trinity upon all of man's inner activities, and life itself.

The perimeter of the lock follows the form of an ennead (group of nine), a design element also used in the pictorial composition of the Adoration of the Magi. The image invites comparisons to Gurdjieff's enneagram. |

|

|

Tellingly, the lid of the trunk is open. This offers us the opportunity to peer into the inner life of the patron. It is the place where he is storing his treasures up: and it is vulnerable, as symbolized by the rat who is stealing his gold. The lid is held open by a pointed dagger; this probably represents the idea that it is only with a pointed insight, that is, a finely honed attention, that a man can see what is actually taking place inside himself. |

|

The presence of the thieving rat indicates that a man's lower parts are always stealing what is good from him: we can be fairly certain that this figure actually represents the lower nature of the patron himself, because he is linked to the figure in the bed by the black nightcap that he wears. |

|

|

The entire vignette, encompassing the trunk, the thieving rat, and the patron himself, paints us a rather touching and perhaps even sympathetic portrait of a man of religious devotion, clutching his rosary, and doing his best to acquire an inner value for himself, all along knowing that the lower parts of his being, covetous and inescapable — they are, after all, deeply embedded in the inner world represented by his trunk — will take from him as much as it can.

|

When we absorb the implications of the trunk and the activity in and around it as a whole, a fascinating picture emerges. The lower forces... including the forces of evil... are crushed by it, as evidenced by the vermin on the right hand side under the trunk. |

| The overall picture is one of an inner and outer life which, although it objectively still contains lower elements (the thieving rat) has managed to triumph over evil. Hell itself, in fact, is banished: it hasn't managed to gain a foothold here. Only a crack in the floor with a few demonic claws protruding from it intimate its presence. |

|

We know that the patron has been marked in this painting is a man of introspection, because he holds the key to his chest, that is, he has access to the nature of his inner life, and can see what he is. The cane with which he holds himself up is an acknowledgment of his infirmity, his weakness, and, directly combined with the presence of the rosary — clutched up against the weakness in itself — he knows he is weak, and needs the spirit of Christ to support him.

As was noted in my analysis of the Garden, the color green is sometimes used by Bosch to represent the best that can be achieved under the circumstances — and that would be more than appropriate as the color for the patron's gown. He is a man who has done the best he can given the limitations of the real world. His attitude is very nearly penitent, and he seems to oddly hold himself away from the gold as he puts it in the bag, as though wary of any covetousness or delusions of merit. One draws, potentially, the impression that this may be the last time he performs this action, as though he were giving the last of his worldly life up in order to take a step towards heaven.

|

Death—the bride in this unqiue wedding-portrait—enters clothed in virginal white: the white of both the nuptial chamber and the shroud. Echoing the implications of the letter, we see that death is cast as a form of marriage, a holy covenant; and not to be feared but, rather, welcomed. It represents, after all, the opportunity to enter heaven. Bosch has thus achieved the unlikely feat of rendering death attractive in this piece, a very nearly winsome lass who peers shyly, yet alluringly, from behind the door. It's a tough trick to pull off, but he does it with aplomb; in fact he even does it with a sense of humor, if we allow ourselves to see his dark wit at work. The arrow is held delicately across death's shoulder like a long-stemmed rose; death is almost cute, and at any rate a bit difficult to fear in this appealing guise. |

The arrow describes a path towards the patron which is extended by its shadow. This subtle device indicates the action of death, death in movement—nearly invisible, but present nonetheless—towards the patron, whose hand appears to be prepared not to reject, but to receive it. This is the portrait of a man of faith, trusting in the Lord to bring him through this ominous moment.

|

Lest we were in any doubt about the overall positive and inherently hopeful message in this painting, Bosch puts an angel directly behind the patron, emphatically claiming him for heaven. |

But what, then, of the apparent exchange between the patron and the golem at his bedside?

The golem can't possibly be tempting the man with money or material; it's too late for that, with the moment of death at hand. So the idea is fundamentally illogical. What we see here instead is the man consciously surrendering his wealth and material possessions to the lower realm that they belong to; rendering, as it were, what is Ceasar's to Ceasar, and leaving his wealth behind in anticipation of the greater rewards of the heavenly kingdom.

The painting, like many of Bosch's legitimate works, is distinctly divided into three realms. In this case, the lower portion, which one might presume to contain hell, is empty except for the armor. The area exculdes any references to hell quite intentionally; the painting is inot really intended to imply that the patron will have anything to do with hell, and we see from the beginning that the work isn't intended as a moral lecture about the dangers of greed and their punishments either. The scenes from the garden confirm that Bosch was capapble of far stronger stuff, had he actually wished to convey such lessons.

The central portion of the painting represents earth, and the patron's final moments there. The uppermost portion of the painting represents heaven, dominated by any airy, gothic vaulted space. The divider echoes the wall at the bottom of the painting.

|

From here, we move upwards into the holy realm of the church. |

|

And the dominant influence here is the figure of Christ, who serves as a mediator of the light of heaven, focusing it in a laserlike beam that aims directly at the patron. |

|

The minions of hell, ever-present but basically powerless under His gaze, become impotent onlookers, physically separated from the patron and his last moments. |

The golem at the foot of the bed and the demon hovering above it are thus visually banished to the sidelines, performing what are no more than ineffective flanking maneuvers.

The potential of hell itself is present here as nothing more than a tiny flame, which serves as a reminder of its potential. |

|

Looking at the three major pieces of territory in the painting, we see that the top and the bottom portions are roughly equivalent in size: both are sparse, even austere. All of the action in the piece is in the central panel; yet using the Zen of minimalism, Bosch has nonetheless imparted a broad range of symbolic understandings in the top and bottom realms.

In the upper portion of the work, which represents, allegorically, the moment after death, we see two alternatives. One, the kingdom of heaven, lies behind Christ, radiant through a tiny window. The way to heaven is, in other words, truly narrow, and only through Christ can we hope to pass into the kingdom of heaven.

To the right of Christ crucified lies a vast, empty territory, punctuated only by a hellish lantern. It's a material—not radiant—territory, vaulted by a flat expanse of dead wood. No signs of life or light appear; the small circular window at the back of the nave is shuttered, implying no exit from this space of eternal darkness. The way of material life and the flesh is empty; it can lead only to hell. Faced with this emptiness, the light and the Truth of heaven are no longer just a possibility; they become a necessity. And the emptiness of this space echoes and underscores the emptiness at the bottom of the painting.

All of life, Bosch is telling us, is a preparation for death. As he introduces our theme, he advises us that life itself is, in the end, empty; and as life draws to its inevitable conclusion, any perceived alternative to Christ and the light of heaven is equally empty.

Like Bosch's other works, the painting is eminently understandable, a story book, and would likely have been easy enough for those of his time to read. The messages in it are deep but straightforward; and it was painted on comission for a specific patron who wanted a positivist contemplation on the nature and meaning of death. It represents another order of memento mori, one not packed with obvious sentimental imagery, but instead infused with questions about our inner life.

This essentially, even magnificently, hopeful painting is, as the symbolism shows, tied to various messages in the Garden; expanding on some of the same themes, it applies them to one man's personal life and his search for meaning in the face of death.

It's a theme, I think, which we can all relate to.